Shaking, extraneous movement and inefficient technique

Introduction

I was going to call to call this article “For goodness sake, don’t do the hippy hippy shake”. But then I realised that this would prompt readers to think that I was referring to my old pet peeve, pre-loading the hip (or the “double hip”).1 This article is not about that subject (which is only obliquely relevant). Instead, this article is about the kind of shaking that results from extraneous and uncontrolled movement (rather than deliberate, if contextually inappropriate, hip loading).

Punching with “hara”

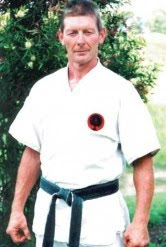

It was in 1988 that I first trained with Graham Ravey, founder of the TOGKA and former deshi of Higaonna Morio. At that training a certain local goju kai teacher (who shall go nameless, but who introduced himself as “Shihan […]”) pulled me aside and said: “You have good technique – but you have no ‘hara’. “Hara,” he told me, “means ‘heart’. Your techniques have no heart.”

It was in 1988 that I first trained with Graham Ravey, founder of the TOGKA and former deshi of Higaonna Morio. At that training a certain local goju kai teacher (who shall go nameless, but who introduced himself as “Shihan […]”) pulled me aside and said: “You have good technique – but you have no ‘hara’. “Hara,” he told me, “means ‘heart’. Your techniques have no heart.” Of course, “hara” is a Japanese term that is used in the martial arts to refer to the dantien or tanden (your centre of gravity located at a point just below your navel). It is not a reference to the heart. But I got his message anyway, particularly when he started to mimic my punches with soft, insipid movements. Then he demonstrated his “hara” version. This involved “powerful” punches: punches that caused “Shihan’s” body to shake almost as if he were convulsing.

Having “corrected” my “insipid” technique, he dismissed me with a wave of his hand and continued speaking with another black belt.

“Phantom impacts”

I knew then, as I do now, that looking powerful and being powerful are 2 different things.2

The same applies to techniques that feel powerful vs. those that are actually powerful. I already knew back then that if you can feel the “power” of your own "air techniques", then something is definitely wrong.

Bear in mind that you are not striking a target, so there is no impact to transfer force back into your body. You should not be feeling any “power” as such. So where does the feeling of “power” come from? Most of the time the answer lies in this: you feel your own “power” because you are reabsorbing it. At least some of your force that was being directed outward is being pulled back into you.

I discuss this in the video below.

I discuss the issue of shaking in basic techniques

Imagine for a minute a bullet flying through the air: it doesn’t gyrate or have sparks flying off it. It just flies. Ditto with a katana (Japanese sword). When a good kendoka (sword practitioner) does an “air cut”, you might hear the “swish” of his blade through the air (caused by the speed of the movement) – but that’s it. It is only when the bullet or the katana strike a target that they experience the force of the impact.

Imagine for a minute a bullet flying through the air: it doesn’t gyrate or have sparks flying off it. It just flies. Ditto with a katana (Japanese sword). When a good kendoka (sword practitioner) does an “air cut”, you might hear the “swish” of his blade through the air (caused by the speed of the movement) – but that’s it. It is only when the bullet or the katana strike a target that they experience the force of the impact.So the kendoka doesn’t gyrate because of the “power” of his air cut. He simply cuts. In fact, the kendoka works very hard to eliminate any extraneous movement or shaking, endeavouring to bring the sword to sudden stop without any “shake”. This is because the kendoka is practising “kime” or focus.3

A karateka also strives to develop kime, and accordingly brings his or her punches to a “dead stop”.4 But if you take the “stop” out of the equation, the karateka’s punches are no different to a boxer’s, especially in this respect: in neither case should the practitioner “feel the power” of a blow that doesn’t land. Both understand intuitively whether an “air punch” is going to be effective, that much is true. They discern this from the momentum generated in the punch, and their experience in gauging the likely consequence of a punch with that momentum. But neither the boxer nor karateka should experience some sort of “phantom impact” that causes “shaking”.

A karateka also strives to develop kime, and accordingly brings his or her punches to a “dead stop”.4 But if you take the “stop” out of the equation, the karateka’s punches are no different to a boxer’s, especially in this respect: in neither case should the practitioner “feel the power” of a blow that doesn’t land. Both understand intuitively whether an “air punch” is going to be effective, that much is true. They discern this from the momentum generated in the punch, and their experience in gauging the likely consequence of a punch with that momentum. But neither the boxer nor karateka should experience some sort of “phantom impact” that causes “shaking”.Shaking as a function of inefficiency

So what is the consequence of shaking and gyrating from a “phantom impact”? Clearly, some of the force you are generating is being applied to your own body. And this component of your force is accordingly no longer available to be applied to a target.5 To apply the same force to a target as someone punching efficiently (without reabsorbing force), you have to generate far more force overall.

Looking at it from another perspective, if you shake with each punch, some of your energy is being used to shake. That energy is not being applied to your task (punching an opponent). In order to land a punch with the same force as someone who is not shaking, you have to use more energy than he or she does. In other words, you are not using your energy efficiently.

It is no compensation to say that you are “more powerful”. Yes, you are being “more powerful” – in that you’ve worked harder in the same time (P = W/T). However you’ve worked harder to get the same, or a lesser, result. The power you’re feeling is, in a sense, a Clayton’s power.6

Shaking and hip use are not the same

I’ve already had some emails on this topic from various martial artists around the world. Some have said: “Well, I’m not “shaking” – I’m just using my hips. I need to do this movement that you call “shaking” because I’m training my hips to deliver powerful techniques.”

If that were the case, then I query why, in the "shaking" way of performing basics, the hip is more often than not being pulled back just before impact. Furthermore, why does this movement cause the whole body to vibrate with the strike? It might not comprise the exaggerated shaking that I perform in my video at the start of this article: it might be a mere "rattle". But it is there nonetheless.

Nor does "returning the hip to position" account for this rattle. If it did, you would see 2 clear movements - not an uncontrolled vibration.

It seems to me that there is more happening here than just necessary hip use.

For that matter, in my video I demonstrate my own hip-assisted punching. I do the same in the videos below. I don’t shake, yet I’m fairly sure you’ll agree that my hip use isn’t all that bad. And I didn’t develop this hip use through “shaking”. I developed it in tandem with the ability to control extraneous movement.

I demonstrate a drill where lateral hip use generates more force. Note that there are 3 hip movements – one for each of 3 punches.

I demonstrate the use of the “rising hip” to generate more force

So hip use does not necessitate “hip shaking”. Consider also the first part of the video below of Minoru Higa (doing the double punches): Yes, there is hip movement, but that movement is confined to the task of the particular punches. The only reason it looks like a “shake” is because there are 2 hip movements – one for each punch. And you’ll notice that the hip movement does not persist after the punch has landed (ie. there is no lingering “rattle”).

Minoru Higa, 10th Dan demonstrating hip use: note in particular the double punches at the start, which are in contrast to the later naihanchin performance.

The double hip isn’t the problem – at least not always!

I’ve mentioned previously that when I refer to “shaking” I’m not talking about the double hip. I don’t think the double hip is the reason so many karateka “shake” when air punching. I believe most shake because they simply haven’t developed the control to move without shaking. The justification/explanation of “hip use” arrives after the fact.

However I did say that the double hip is obliquely relevant to this article, and here’s why:

In some schools virtually every basic and kata technique is performed with a hip pre-load. And when you pre-load I think it goes without saying that it is almost impossible to avoid shaking. So if you spend all your time doing the double hip, and if you never practise isolating your punch (without hip movement), you never learn to move without shaking.

In other words, focussing undue attention on developing the double hip might lead to more than contextually inappropriate hip use: it might inhibit the development of a very important ability. The ability to control one’s body.

It’s all about having control of your own body

The problem I have with “movers and shakers” is that I feel their shaking is a often a cop-out. They aren’t aware of (or won’t admit) the importance of learning to control their bodies so as to eliminate extraneous movement. Instead, they focus on the “power” they feel (and others see). They ignore their own lack of attention to detail and invoke the “bigger picture” of “effectiveness/practicality”, while deriding controlled punches as “quaint”, “overly formal/stylised” or as “show karate”. As the aforementioned “Shihan” said to me: “it might not be pretty, but it works.”

Quite evidently there are many “untidy” karateka out there who are formidable fighters (“Shihan” wasn’t one of them, by the way). As in boxing, or any other combat discipline, there are those who are technicians and those who are brawlers. And brawlers can be viciously effective.

But this doesn’t lessen the importance of striving for efficient movement. Such efficiency is what gives the smaller, weaker and less aggressive person the chance to hold his/her own. Efficient technique is, self-evidently, desirable, particularly to the thinking person. And extraneous movement in the form of shaking is the opposite of efficiency.

“Shaking” isn’t practical in any event

But quite apart from the above, I’m fairly certain that “shaking” doesn’t make sense – even to the brawler.

I’ve noticed that “movers and shakers” will air punch one way, and punch a makiwara/bag/shield in another.

Once again, consider the first video in this article. In it, you will note that I demonstrate how punching a target does not necessitate “shaking”. If there is any “shake”, it comes entirely from the force transmitted from your target into your body when you impact. The more resistant the target, the more you will experience this force. But if the object is not particularly resistant (eg. a phone book or a person’s face!) you shouldn’t experience much impact force at all. And when you are punching air, there should be none.

I haven't been able to find any "archetypal" examples of shaking on the net. It seems that pretty much the only karateka to post videos of basic techniques are the shotokan practitioners, who are generally very good at basics.

With that in mind, consider the punching in the following video: It isn't the most obvious case of "shaking". And it looks powerful, I'm sure you'll agree. It looks so powerful that some readers might start to wonder whether I've lost my marbles with this argument. After all, isn't his power self evident?

An example of punching with some shaking (not the most obvious example, but there are few on the web). The practitioner looks very powerful indeed. And he probably is. But I think it is self-evident that he is reabsorbing an unnecessary component of his (substantial) force.

But why does his punching look so powerful? I think it is because the practitioner is absorbing a significant component of his own (substantial) force (causing him to "shake" at the point of impact). Otherwise, why would it look "powerful"? He isn't hitting anything! Again, the bullet and sword analogies spring to mind.

But why does his punching look so powerful? I think it is because the practitioner is absorbing a significant component of his own (substantial) force (causing him to "shake" at the point of impact). Otherwise, why would it look "powerful"? He isn't hitting anything! Again, the bullet and sword analogies spring to mind. An effective punch needs just 2 things: mass and velocity. Accordingly, an air punch shouldn't look "powerful": it should just look fast.

A well focused karate punch should have the added feature of stopping suddenly. But such a stop doesn't require shaking, gyrating or other "visible power".

The above karateka is a very hard hitter; of that I'm certain. But in my opinion this video is not illustrative of the way he would punch a target. Like many karateka, I'm sure he has developed 2 ways of punching: one for "air" and one against targets.

The above karateka is a very hard hitter; of that I'm certain. But in my opinion this video is not illustrative of the way he would punch a target. Like many karateka, I'm sure he has developed 2 ways of punching: one for "air" and one against targets.I don't have a video of the gentleman above punching makiwara, but if I did, I bet it would look something like the video below. You'll notice that the shaking is entirely absent - except for the shock from the actual impact.

Yahara Mikio demonstrating makiwara. Note the lack of shaking, except that caused by impact.

“Shaking” is bad for you

I have tried virtually everything in my martial arts career. I’ve even tried “shaking”. But there is a major reason, apart from inefficiency, that leads me further and further away from it: It hurts.

Shaking the body means you’re absorbing a lot of your own force. This force has to do some damage – particularly if you’re punching very “hard”. Over the years I’ve found that this kind of “hara” punching causes my tendons to inflame, particularly after a long session.

The major problem areas are the shoulders and the elbows. The elbows are particularly problematic if you lock them when you punch. Other parts of the body can also feel the effects: I’ve hurt my back (particularly my lower back) and even my neck.

For a brief period, I thought that “shaking” might be good for you: I thought it might “toughen you up”. I was wrong. If you’re interested in conditioning your body, there are far more effective and scientific ways of doing it. Uncontrolled, explosive actions that lead to extraneous movement are a recipe for disaster – especially to an aging body.

Distinguishing Chinese “shaking” arts

Some schools of Chinese martial art teach a kind of “shaking” in conjunction with other types of movement. I’m thinking in particular of “shaking crane” and the “fajin” of the internal arts.7 I don’t intend to dwell on this subject for too long, but I will make the following observations:

The role shaking plays in these arts is, in my opinion, very different to the “shaking” one so often sees in karate basics. For a start, the shaking does not occur with each technique. It is an occasional thing. A taiji practitioner for example learns to move without any shaking at all and spends the vast majority of his or her time perfecting such “non-shaking” movement. Occasionally he or she will demonstrate “fajin” – an explosive release of energy. But this has little in common with absorbing your own force over thousands of standing basic punches.

Second, the type of shake is very deliberate. It is not uncontrolled. It is not a by-product of your power – it is the goal. I’ve often heard it said that the action approximates that of a dog shaking itself dry. This is a far cry from a shake produced by a “phantom impact”.

Rattle and hum: you too?

Almost every karateka I know (including yours truly) has a little "rattle" with his or her standing punches. This "rattle" is hardest to avoid in standing basics.

I reject completely the notion that "tremendous power" in punching necessitates shaking, just as I reject the notion that the shake is deliberate hip use. In most cases the extraneous movement simply comes down to this: the student has insufficient control over his or her own body to move without it. I believe we should all be striving continually to achieve the greatest possible level of this control so as to achieve the greatest possible efficiency in movement.

So how does one learn to eliminate extraneous movement?

The first step is to acknowledge that it is there.

Most karateka I know are unaware that they are shaking. Consider the video below: the practitioner is clearly quite skilled, but he would probably reject out of hand that he is "shaking" (at least, to any significant extent). True, it is nothing like the shaking I've seen elsewhere. But it is still not like makiwara punching: the body still "rattles" as each punch lands. Compare this gentleman's slow punches with his fast punches, noting in particular how much his belt moves when he punches fast (where it doesn't move at all when he punches slowly):

The shaking in this video is typical of examples on the web. It is very mild. However it is a kind of shaking nonetheless. Note the "rattle" with each fast punch (watch the belt move). Contrast this with the makiwara punching above or with my controlled punching in the first video.

I'm sure you'll agree from my opening video that I have gone some way at least to minimising such extraneous movement. And I believe that I have done so without losing power. I make this observation merely in order to evidence that it isn't "impossible" as many seem to think. The "rattle" is not an inevitable side effect of standing basic punching.

The second step to eliminating extraneous movement is to use traditional stances. As I demonstrate in my opening video, shiko dachi (sumo stance) is excellent for this: If you hold a stable shiko dachi, you simply cannot "shake, rattle or roll". You are forced to move without extraneous movement. This is, in my view, one of the most important reasons for basics performed in stances.

Consider, by way of contrast, the level of extraneous movement in following video:

Extraneous movement doesn't often manifest with slow punching; when it does, it doesn't bode well for the efficiency of fast punches.

The karateka bobs up and down with each punch despite the fact that he is punching quite slowly. I strongly suspect he would move a lot more if he were punching hard and fast (given that this is when one loses control). Here is one student who would benefit from practising basics in deep, stationary stances.

"Does it matter," I hear you ask, "if you don't have 'perfect' technique?" To the extent that we should all be striving to improve our skills, I think it does. If you can't control extraneous movement, you don't have much control over your own body. As a result, you can't be efficient and you can't avoid telegraphing (think of the wind up of the "power" karateka featured earlier, or the "bob" of the chap in the above video).

Whether you think this "perfection" is important or not depends on whether you see yourself as a "brawler" or technician". I incline very much to the technician. I think you have to fight smart (or as smart as you can).

As an exercise, do some basic punches in heiko dachi (parallel stance) and try not to shake at all. If you can't, ask yourself why. Drop into a shiko dachi and try it there, then go back to heiko dachi. It is my view that this is what standing basics are primarily for - not for "double hip" practice. I'd wager that those who scoff at my suggestions simply don't have the control to avoid shaking - or have never even tried to avoid it.

A summary video in which I demonstrate some techniques with minimized shaking or other extraneous movement

Conclusion

If you perform your basics with a “shake” in each movement, ask yourself whether this is deliberate and controlled - or the opposite.

The fact that shaking is quite common (we all have it to some extent) doesn't lessen the importance of minimising your extraneous movement through controlling your body. I wrote this article to alert karateka to this issue, not to denigrate anyone.

I get the feeling that for most karateka, any “shake” that accompanies their basic punches is an unconscious by-product of trying to be “powerful”. In reality, force is determined not by how “hard” you punch but by the simple variables of your mass and your velocity. “Hard” punching translates to punches that you “feel”. You feel them because you’re reabsorbing some of your own force. And force that is reabsorbed is force that isn’t being used productively.

So for goodness sake – don’t do the hippy hippy shake.

Footnotes

1. See my articles:

- “Whole lotta shakin’: pre-loading the hips”.

“Whole lotta shakin’: an addendum”.

“Whole lotta shakin’: contextual hip use”.

“The importance of flow”.

“Flow: why it is an essential component of kata”.

3. See my article: “Kime: soul of the karate punch”.

4. See my article: “Karate punches vs. boxing punches”.

5. See my article: “Hitting harder: physics made easy”.

6. For a discussion about what “Clayton’s” means, see my article: “More about the Clayton’s gap”.

7. See my article: “Understanding the internal arts”.

Copyright © 2010 Dejan Djurdjevic

Hi Dan,

ReplyDeleteAt the end of the punch, when I tense up, it also seems like I'm absorbing the power of the punch by stopping it - aren't I hurting myself by stopping the quick motion so abruptly?

Also, when punching, should the shoulders be straight, or can they portrude forward a little with the punch.

Hi Mike.

ReplyDeleteStopping your punch with your muscles is fine - it is part of kime. Have a look at my article on this topic (there's link above).

Stopping a punch abruptly is okay because you are simply stopping - not pulling force back in. You know how much force you pull back by reference to how much you shake.

Take a look at my "non-shaking" punches in the video above.

That said, I've hurt my shoulders and elbows by punching fast before I've warmed up, so you always have to be careful.

When punching your shoulders should be rounded a little. Do a push up and pause at the top. Note your shoulder position - they are not square/straight, nor are they protruding. They are in what is sometimes called the "C back" position. That should be how they should be when you punch.

I'm planning to write an article on the C back sometime soon.

All the best.

Dan

AMAZING.

ReplyDeleteThis has single handedly worked wonders for my own punching...Now I understand the proper use of hip and it makes sooooo much sense. I used to be into the exaggerated hip thingy because I could do it and it made me look cool in the dojo. Then I started paying attention to Wing Chun, where some of the good teachers were saying all the extra hip movement only "felt" powerful, but wasn't. The I found your blog! Now I see the light lol

I do have a question. Is it proper technique to keep the shoulders down while punching in Karate? It seems easier to transfer power form the legs when they are, but boxers lift their shoulder to cover their chins, which seems practical as well.

Thanks Joshua!

ReplyDelete"Is it proper technique to keep the shoulders down while punching in Karate?"

Yes - in basic technique. In basic technique you are learning to control your body. This means no extraneous movement: the techniques are isolated.

A lifted shoulder girdle in no way helps your punch. In fact, it creates a little bit of tension in your shoulders which can slow you down. You have to relax any muscular tension before you can move. Otherwise it is a bit like driving with your brakes on.

"It seems easier to transfer power form the legs when they are, but boxers lift their shoulder to cover their chins, which seems practical as well."

Boxers will raise their shoulder girdle, but I'm fairly sure that most of the great knockout punches feature relaxed shoulders. Ali's "float like a butterfly, sting like a bee" comes to mind. Ali used to keep his shoulders relaxed most of the time (he also kept his guard down!) Most boxers will raise their shoulder girdle to help shield against punches, so this is a defensive compromise. Karate uses less a shield and more interception with deflections, so the issue does not arise.

Thanks for clarifying, that's what I was thinking but I wanted to make sure. I tested it out and found that when striking an object with a relaxed shoulder actually creates a more stable strike as well.

ReplyDeleteI noticed, especially with Shotokan, that Karate really is based on timing and interception just like you said. I think the idea that Karate blocking is supposed to function like western boxing blocking is what leads people to think karate doesn't work. When in reality Karate functions differently and not many people, apparently, are aware of this.

Hi Dan,

ReplyDeleteI'm wondering if the reason why a person may not be shaking when striking a target is because the power is transferred into the target; and by implication, the reason they shake when air punching is because that power is not transferred out of the body, hence the shaking.

A boxer punching a bag punches harder, I believe, than when he does shadow boxing. If he were to punch the air as hard as he punches a heavy bag he would fling himself off balance (and cause tremendous associated "shake"). Therefore he tones down his shadow boxing, i.e. air punching.

Don't you think it possible that when a person is aiming to illuminate shaking that he is merely toning down his power like a boxer does when he moves from punching a heavy bag to punching the air?

No Soo, I think that would be contrary to physics. An impact against a highly resistant object (a brick wall) will cause you to shake as you hit it. An object like the one I hit has little resistance, hence I don't shake from the impact.

ReplyDeleteThink of a car driving along: it doesn't shake. If it hits a brick wall, it shakes! The same laws of physics apply to your punch.

I forgot to say: the boxer follows through with his punches, so his shadow boxing is very different from his punching. Karateka don't follow through - they focus their punches. See my article on this subject.

ReplyDeleteIf you did a big boxing follow through punch, you wouldn't shake at all. You'd just overbalance. If you fell, you'd shake, but that is because you've hit something (the ground)! Until that time, you wouldn't shake at all.

Great article. I'm learning a different system, but I'm sure I can apply some of what you wrote to my own learning (or at least try!).

ReplyDeleteHow can you tell the difference between tensing at point of impact on a punch and the shaking aspect? It's one of those I know it when I see it in others, but are there some guidelines in solo practice?

ReplyDeleteAs I say, do some punches in deep horse stance (shiko dachi). That should help you discern the difference between shaking and tensing at the point of impact. It isn't possible to shake if you are holding a proper shiko dachi.

ReplyDeleteOn a side note following your comments on Chinese Internal Arts, I was attending a seminar a while back where the teacher said that often times students will ask him to display fa jin to them, but to do this in mid-air is impossible, because it inevitably needs a force to react with. To execute fa jin in mid-air with no resistance seems to be much different than when with the required resistance.

ReplyDeleteFrom a Seido Karateka:

ReplyDeleteI was very disappointed by said Graham Ravey's response to this video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RoGOSSy5lA

Yes, most of the karateka in the video may not be of the same caliber and quality as those of IOGKF (much respect to Morio Higaonna) or TOGKF, but they don't warren such disrespect. After all, they are working on themselves, striving to improve and polish their technique.

Osu and keep up the great work!

Thanks Seido karateka. Around the time your comments I heard from a number of different sources that someone purporting to be Graham Ravey left nasty comments on their Youtube videos.

ReplyDeleteNeedless to say, this is not at all like Graham. Moreover, reading the comments it is clear to me that he did not write them; he simply doesn't speak like that. I am fairly certain someone hacked into his account.

Yes - it isn't Graham. It isn't even his account. Rather someone has set up a parallel account using his name.

ReplyDeleteSee this thread

Hmm, really interesting article.

ReplyDeleteWhat's your understanding of the function that (correct) hip movement plays in throwing a good punch?

I'm familiar with at least two theories:

1. Geoff Thompson (in his book 'Real Punching') seems to advocate what I'll call a "hip pivot." This is where the pelvis drives towards your target and remains extended as your punch impacts.

What we see (my interpretation, Geoff didn't say this) is the punching side of the body (hip, torso, shoulder) rotating forward more or less in unity towards the target around the vertical axis.

2. Marc MacYoung (in his book "Secrets of Effective Offense" and also I think on his website) advocates the hips as a secondary component: the power is generated from weight transfer, and magnified with a "hip flick" which serves to accelerate your limb into the target. Important difference: the hip relaxes and retracts after it 'flicks' forward.

(I've seen people take this further and try to argue that you can actually whip your hip back again, which I suspect you'll cover in some of your related articles. I've never been able to make this work personally.)

On what I take to be Marc MacYoung's view, the hip (and your punch overall) seems to function as more of a whip.

There are a few ways of playing with those two options (and I suspect that they can be unified, I'm still playing around with it), but I have found that adopting the 'hip flick' results in some residual movement as the hip relaxes.

(The obvious way to try to unify those two options is to try to adopt some kind of "flick and stick" action in the hip on the punching side.)

So what's your view? Do you accept the "pivot" vs. "flick" distinction? Effectively you have a rotational punch vs. a whipping punch. If you accept the whipping punch as an option, is it possible that (some) of the residual movement you identify is just the hip rebounding from its flicking action?

Or do you believe that the hip really has to "pivot" and stick at the point of impact in order to properly preserve structure?

(PS I have no particular agenda here: I'm a fan of whichever method gets me hitting harder, so interested in your response.)

Hi Michael

ReplyDeleteI have covered elsewhere my view that the hip should be used in what I call “staged activation” of body parts - moving from the larger body parts to the smaller. So your body core will move first, both forward and rotationally at the hip, leading to your shoulder moving, leading to your arm moving, to your fist landing.

I don’t subscribe to the “whip” or “flick” analogy. To me, only some techniques are truly “whip-like”, namely a back fist (uraken). That said, all snap techniques have more in common with a whip than they do a ramming rod. This includes front snap kick, jab etc.

Where does the hip fit in with this? Well, it doesn’t matter whether it is a “snap” (ie. a whip-like movement) or a “follow-through” (ie. a big cross punch or a roundhouse shin kick to your opponent’s thigh): In each case the hip acts through staged activation; it is (or should be) the first joint to move, followed by a succession of smaller joints.

Marc MacYoung is right in saying that forward momentum plays a big part. However you don’t just run into your opponent. To deliver a truly powerful blow, you need to have forward momentum timed correctly with staged activation of body parts.

You see this in a javelin throw: The thrower will run forwards, building up forward momentum. At the point of release he will start to turn his hip, then his shoulder, then his elbow, and finally (and most crucially), flick his wrist. Each step is important - even the last. If one link in the chain is missing, you fail to impart the full force of your potential.

Where does this fit with “pivot” vs. “flick”? I regard this distinction as unhelpful. Whether the full movement is described as a snap or thrust doesn’t affect the role of the hip in its outward phase. It only affects the retraction phase (after your strike has landed). So with a snapping technique (eg. a front snap kick) your hip will retract with the snap back. It won’t “stick” at the point of impact longer than the time of contact. With a follow-through (a front/side thrust kick, a cross punch, a roundhouse kick to the thigh) there will be longer contact time, and therefore longer “sticking” before the hip retracts. It’s horses for courses; there is no general rule for whether the hip should “stick” or not. The latter simply depends upon which strike you choose.

Which “hits harder”? Well, follow through strikes (ie. where your hip sticks) impart more force. I cover this in my article on “Hitting harder: physics made easy”. However, “hitting harder” isn’t your only criterion for choosing a strike. See how Lyoto Machida and Anderson Silva have recently used snap kicks for knockouts (where follow through kicks impart far, far more force). Why did they use them? Because they were the best weapon for the occasion. You have to weigh up whether you can land your blow, not just how forceful it will be. A strong blow that misses or is blocked or that never reaches its target because you’re hit first, is clearly of no use to anybody. A less forceful blow that lands can still be determinative, if you land it and do so on the right target. In the case of a front snap kick (fairly low in pure force), it is very effective when applied to the face, for example.

Thanks for reading and your contribution.

Hi, Dan.

ReplyDeleteYour post seems so common sense that, if you hadn't written it, I'd have thought it wouldn't need saying!

Just as with your javelin thrower, our German longsword strikes will not allow for extraneous body movement. When you or your opponent are striking with a 4' lever in two hands, 2-4 strikes, parries, or aborted actions to cover unexpected attacks, there is no time for pre-loading the hip -- each step or hip movement must fulfill a purpose, and no more. So our strikes follow through about 3-6" into the opponent, but we gauge our force for only that much (3" penetration is ample to reach bone and organs). The sword begins decelerating upon the projected point of contact and immediately begins to be drawn back into the next action.

Sometimes for entry strikes to create an opening, we pull back at or just before the instant of blade contact, and the minutely premature hip chambering is used to further slingshot the tip in a flick past the opponent's guard such that he perceives a continuation of the strike even as you chamber for your second strike.

But it's all like you say. When we're in good form, our "air punches" terminate in a guard stance just so, like a ball thrown in the air that comes to rest on a shelf just as it rolls over the apex of its arc.

I have loved your thoughts and videos on baguazhang -- I haven't found regular instruction to suit my 30-70 ratio of concept-to-practice in Texas, and have chosen to work from videos showing first principles and applications, supplemented by my Northern Mantis and other body awareness / martial arts training.

Your thoughts have been considerably more helpful than Yang Jwing-Ming's text on baguazhang.

All the best,

Dakao

Thanks for your comments Dakao.

ReplyDelete"Your post seems so common sense that, if you hadn't written it, I'd have thought it wouldn't need saying!"

I agree, but it's strange how often I encounter skewed perspectives based on strange interpretations and interpolations - all stemming from a failure to reconcile "formal" basic practice with application. Ockham's razor suggests the simplest solution is the correct one, yet people will nonetheless create mind-boggling theories to support another unnecessarily complex "solution". As a result I've found it necessary to dedicate a fair portion of my writing to outlining what I consider to be the bleeding obvious!

"Just as with your javelin thrower, our German longsword strikes will not allow for extraneous body movement. "

And it is clear to me that (as one would expect) all martial arts have the same physical underpinnings, whether they be of Western or Eastern origin - regardless of what some people might see or think. The differences are superficial. After all, a human being can only move in so many ways.

"When we're in good form, our "air punches" terminate in a guard stance just so, like a ball thrown in the air that comes to rest on a shelf just as it rolls over the apex of its arc."

A very insightful analogy. Thanks for reading and for your contribution.

Hello Dan,

ReplyDeleteI have followed both your blog and your yt. account for a long time and I share many opinions with you about ma's, to the point that I consider you a reliable source of knowledge on that subject, but here I am not sure of what you're saying: obviously, if we talk about staged activation punches, as a boxing cross, I agree with you; but I am not so sure that "shaking" could be totally eliminated from what, for example Mr.Montaigue calls Fa jing, or what these men, who seem (although it's hard to say that from a video) profficient at internal arts explain in this Yt. video http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ImebtD800M say that is "internal way of delivernig power".

I have read elsewhere, also, (from mr.Montaigue) that internal striking is powerful because you use your whole body as a whip, which (to me, at least ) implies shaking.Mr An Jian Qiu, in this video http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ol32eUQ0DhA (I think is Ba Ji Quan) uses the "whole body whip", which(to me, again) implies certain degree of "shaking". It might happen, also that the "shaking" about which I am talking about is not the shaking that you're talking about, bit I reckon that I'm quite lost on this subject.Please forgive my poor English, as I am from Spain.

Thanks for reading.

Hello and thanks for your comment.

ReplyDeleteShaking is extraneous when it is not both deliberate and controlled.

So for example, if I choose to shake, that's all well and fine. But can choose not to shake? That is the question. If you "choose" to shake, but cannot help but shake in every movement (as frequently happens) then your shaking is just the result of lack of control.

If you can move with total efficiency and choose to do a fajin "shake" on certain movements, then this is very, very different. The shake is a controlled release of force in a small movement. The small movement and the amount of force necessitates a certain "shake" as a by-product. But with, say, a normal full-length punch or kick, there should be no shake. For example, would you shake doing brush knee?

I hope that answers your query! Have a happy new year!

Dan,

ReplyDeleteI read this article when you published it, and knew within a few minutes that you had written something amazingly helpful. This article is, in fact, the most helpful one for me. I now understand why I felt so tired after a few punches, how my punches differed from those of the GM at my dojang, and why my shoulder is in so much pain from punching. Thanks to you, I have stopped this dangerous habit, and can now work on rehabilitating my shoulder.

Thanks,

Mohammad Raza Khan

I'm so happy to hear that Mohammad. The very reason I write these articles are because I hope to contribute to martial debate, if not to the actual "knowledge database". It seems pointless to sit by and watch others make the very mistakes I've made over the years.

ReplyDeleteThanks again, and be well.

Dan

Khan's problem is very similar to some people who ask questions about martial arts. They have shoulder, neck, or elbow problems and want to know how to fix it.

ReplyDeleteMore than half of these come from air punching, not makiwara or bag work. And it usually seems to happen after a student either has a lot of muscle power in the arms or a lot of conditioning in punching. The newbies that hesitate as if they are punching through jelly, don't exert enough force to worry about it.

Several years ago I also experienced these painful results. It seemed like it got worse the more I practiced. So I stopped. I only utilized slow movement training. I could only handle a single fast movement speed before things started to hurt, even after weeks of rest. It wasn't until fairly recently that I was able to figure out how to create energy sinks on my body or to the ground, to take this energy and shunt it away when air punching. Hitting bags or targets never had this issue.

I believe most of my thanks would go to Jin Young, for pointing out the importance of nailing down the shoulders and aligning the elbow. Punching the external way, using only my arm speed or strength, was something I had been using for awhile. I don't think I had even realized why the pain had disappeared, until someone had the same problem and asked me for help. Then I looked back and realized that that might have been it.

I do not agree entirely with Dan's definition and usage of shaking, but that's mostly due to variances in definition and the fact that there are different kinds of shaking. Some good, some bad, some neutral. Usually, if it doesn't hurt, it's at least not bad.

I have yet to figure out if what I am now doing and what Taiji Chuan and Bagua water fall fajin exercisers do, are the same. It kind of looks like the same, but the only real test I will accept is feeling and practical results. I need someone as the human target and directly compare my hit to an internal users' hit, to compare the differences in feeling. None of this Fight Science "data interpretation" with the crash dummies. That data can be interpreted in a number of different fashions. Even when I hit bags and people say that they can feel the power of my strikes, I don't even know what that means because I don't feel. If I don't feel it , it pretty doesn't exist for me. Just somebody's subjective interpretation. If I hit them and they flinch away, that's their subjective pain threshold. Which I am pretty certain is leagues below my own. If I hit myself, that's not even 50% of what I could, so the results do not scale as I can't make them scale. Asking others to hit me doesn't work either, since most of them have no idea how to hit using external striking methods, let alone Internal methods. But I do like Kyokushin and Kajukenpo's idea of hitting people to toughen them up. Although I prefer to use a far less injurious version. I primarily use it to test beginner's striking power, so I can directly gauge what it is they are lacking. Also toughens up their mental focus so they can actually hit people... without being angry.

Until I figure these out via personal experimentation, I cannot fully agree with Dan's description of shaking here.