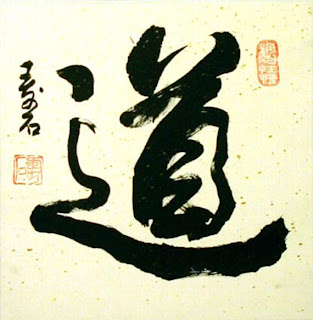

The internal arts and Daoism

I came to the internal arts through both the study of physical martial arts training and philosophical reading.

I came to the internal arts through both the study of physical martial arts training and philosophical reading. It was in the mid-80s while watching the BBC television series “The Way of the Warrior” (in particular the episode on Hong Yi Xiang and the internal arts - see the full episode embedded below) that I first learned that the earliest of the internal arts – xingyiquan – is said to be a physical manifestation of the the Chinese classic known as the Dao De Jing (Tao Te Ching) – “The Way and its Virtue/Power”. I was familiar with this and other Daoist texts and commentaries from the many hours I spent poring over them in the university library (while was meant to be studying other things!). Coincidentally, my teacher Bob Davies was studying xingyiquan with Hong Yi Xiang at around that time.

Internal arts such as xingyiquan are a physical embodiment of Daoist principles such as "wu-wei" - the way of least resistance (hence the title of this blog). They use use "natural" action by "going with the flow" and in so doing exploit all the available natural forces (including the opponent's force) against the opponent (the latter is similar in philosophy, but not execution, to that of aikido). I remember being fascinated by that episode of The Way of the Warrior - not only by the brutal technical brilliance and sophistication of the internal arts, but also by the fact that they were part of an unbroken philosophical tradition that stemmed from one of the earliest civilizations on Earth.

The Dao De Jing is just one of many Daoist texts, although it is generally regarded as the "cornerstone" of this philosophical tradition. Broadly speaking, this text (one of the first books ever written) deals with "man in nature". It is very “elemental” and relatively “straightforward”, yet as profound a piece of philosophical writing as you’ll ever find.

It is still, to my eye, the archetypal “ancient wisdom” that humans seem to crave and search for (in vain) in religious texts which variously contain copious amounts of irrelevant, irrational and sometimes abhorrent dogma, passed off as some sort of esoteric “wisdom”.

Even after all these years, I still am in awe of the author (Laozi or Lao tzu) or, rather, authors (because there were probably many contributors over the millennia) of this little book of wisdom. This is doubly so because he/she/they wrote it so many years ago (the earliest copy dates from more than 2000 years ago). It does not impose any moral codes nor mention any deity. Its basic, straightforward and common sense (if often seemingly counter-intuitive1) advice is still starkly pertinent today. I discuss some of the lessons of this book (and my application of them in daily life) in my articles “Bar stools and mosquitoes: more about wu-wei”, “The sight of 2 hands clapping: wu-wei and the threshold for aggression” and “Wu-wei vs. Pacifism and appeasement”.

The full episode of the BBC series "The Way of the Warrior" relating to the internal arts and Hong Yi Xiang

There are of course many other Daoist texts including the Zhuangzi or Chuang tzu (a largely pragmatic, common sense text that also contains one of the earliest theories of what we would today describe as the “law of conservation of energy/matter”2 and some meditations on the origin and nature of matter that are startlingly in keeping with our latest scientific theories3) and the Liezi or Lieh tzu (a less pragmatic text with greater “pacifist” or “quietist” leanings). All of them are fallible and very human documents. That is what makes them so special. They don’t purport to be some sort of dogma or “word of God”. Like the words of Socrates, they don’t depend on the historicity of their purported author (in this case, enigmatic philosophers called “Laozi”, “Zhuangzi” or “Liezi”). That is because the lessons they contain are undeniably the product of considered reason over a great period of time.

I think it is hardly surprising that these ancient texts should contain useful and sage advice: They are the product of a sophisticated culture – one that was literate and advanced in its philosophical traditions.

These ancient people didn’t just whittle sticks in their spare time. They had the same brain power we have today. Yet, being closer to elemental nature, and uncluttered with the information overload today, it seems entirely reasonable that they might have ruminated on matters that we often fail to consider in our modern lives – and that over a period of thousands of years of consideration, commentary and evolution, reached some conclusions that are useful to this day. They had more time to spend on such “basic” philosophical issues, where in today’s world we are clouded by a thousand different competing paradigms. In some ways, our lives are far too complex to ponder the simplest things. For that we would have to “go back to nature” – which is precisely what the early Daoist writers could do (and are reputed to have done). They were writing at a time when man was just emerging from a hunter-gatherer world. That a writing system existed at this time in China is fortuitous as it enabled profound insights into man’s place in the natural universe to be recorded.

These ancient people didn’t just whittle sticks in their spare time. They had the same brain power we have today. Yet, being closer to elemental nature, and uncluttered with the information overload today, it seems entirely reasonable that they might have ruminated on matters that we often fail to consider in our modern lives – and that over a period of thousands of years of consideration, commentary and evolution, reached some conclusions that are useful to this day. They had more time to spend on such “basic” philosophical issues, where in today’s world we are clouded by a thousand different competing paradigms. In some ways, our lives are far too complex to ponder the simplest things. For that we would have to “go back to nature” – which is precisely what the early Daoist writers could do (and are reputed to have done). They were writing at a time when man was just emerging from a hunter-gatherer world. That a writing system existed at this time in China is fortuitous as it enabled profound insights into man’s place in the natural universe to be recorded.The art of baguazhang is, by contrast, more a neo-Confucian work, marrying Daoism ("man in nature") with Confucianism ("man in society"). Without abandoning the elemental roots of xingyiquan and the Dao De Jing, it succeeds in reconciling these with the myriad social rules of dealing with what in the West is described as the social contract. It is associated with the classic known as the Yi Jing (I Ching) - “The Book of Changes”. Baguazhang is said to be a physical embodiment of this book, with its 8 trigrams and 64 hexagrams. Bagua, on one view, is like xingyi with all the mathematical permutations extrapolated in the form of a matrix.

Taijiquan is, of course, a combination of both xingyiquan and baguazhang and embodies the most recent interpretation of Daoist thought in a physical and philosophical sense. It is, at once, far more sophisticated in its combinations, yet far easier to perform (on a macro level). My suspicion is that it is much harder to master at its most subtle levels, truly making it the pinnacle of understanding human movement in the dynamic context that is fighting.

Footnotes:

1. I often think of Daoist advice as running exactly opposite to that which you would normally do!

2. See this quote from the Zhuangzi Chapter 18:

- “When she just died, how could I not feel grief? But I looked deeply into it and saw that she was lifeless before she was born. She was also formless and there was not any energy. Somewhere in the vast imperceptible universe there was a change, an infusion of energy, and then she was born into form, and into life. Now the form has changed again, and she is dead.”

- “All things sprang from Non-Existence. Existence could not make existence existence. It must have proceeded from Non-Existence. And Non-Existence and Nothing are One.”

Copyright © 2012 Dejan Djurdjevic

The Hobbes thing is unnecessary to your point, and anyone familiar with Hobbes' work will get distracted by the fact that you're not using his idea correctly. Hobbes' "state of nature" was a hypothetical situation where any man was in a competition of survival with every other man, and was used to illustrate why man needed governments and civilization. It is not synonymous with ancient civilization; as far as we have recorded history, man has never actually been in Hobbes' state of nature. A minor point, but to anyone who knows the text this is distracting.

ReplyDeleteFair enough Anonymous. I'll remove it. Thanks for reading and your input.

ReplyDeleteGreat post Dan,

ReplyDeleteI became aware of Daoism during my travels to China when I was taught Taijiquan by and elderly man in the park over the course of two weeks. Later through my study of Xsing Yi I became a practioner of Daoism.

Love the blog and enjoy every article.

Thanks for your kind words and input! Much appreciated!

ReplyDeleteWhat the ancients achieved can be considered enlightenment.

ReplyDeleteThere are several paths to enlightenment by my research.

1. Understanding and comprehending the knowledge of the ancients, and then applying it to modern life. (Aristotle would apply, being a student in a line unbroken from Socrates and learning from Plato's anti-democratic feelings)

2. Facing mortal combat, life and death situations, multiple times to tap into the absolute truth of what divides life from death (Miyamoto Musashi and partially Sun Tzu)

3. Meditating without social interference, in opening the third eye and perceiving nature and existence as it is, without human prejudices and logic. (Also known in religion as not worshipping idols of God, and this has been achieved by probably the greatest number of monks, Taoist or Buddhist, Indian as well. Problem is, because they gained this insight through subconscious thought and meditation, they could not explain it in words or writing to others)

That's about it really. If anyone else knows any other ways to achieve enlightenment, I'd like to hear them.

Ymar, you should start a blog. That way, you could really record your ideas in one place.

ReplyDelete